Revoluções

Revoluções, a nova criação de Né Barros, cruza coreografia, instalação, imagem e música e conta com a participação do coletivo Haarvöl e da Digitópia da Casa da Música.

Todas as razões para fazermos uma revolução estão aí. Não falta nenhuma. O naufrágio da política, a arrogância dos poderosos, o reinado do falso, a vulgaridade dos ricos, os cataclismos da indústria, a miséria galopante, a exploração, o apocalipse ecológico… de nada estamos privados, nem sequer de estar informados de tudo isto…Todas as razões estão reunidas, contudo, não são as razões que fazem as revoluções; são os corpos. E os corpos estão diante dos écrans.

Comité Invisible

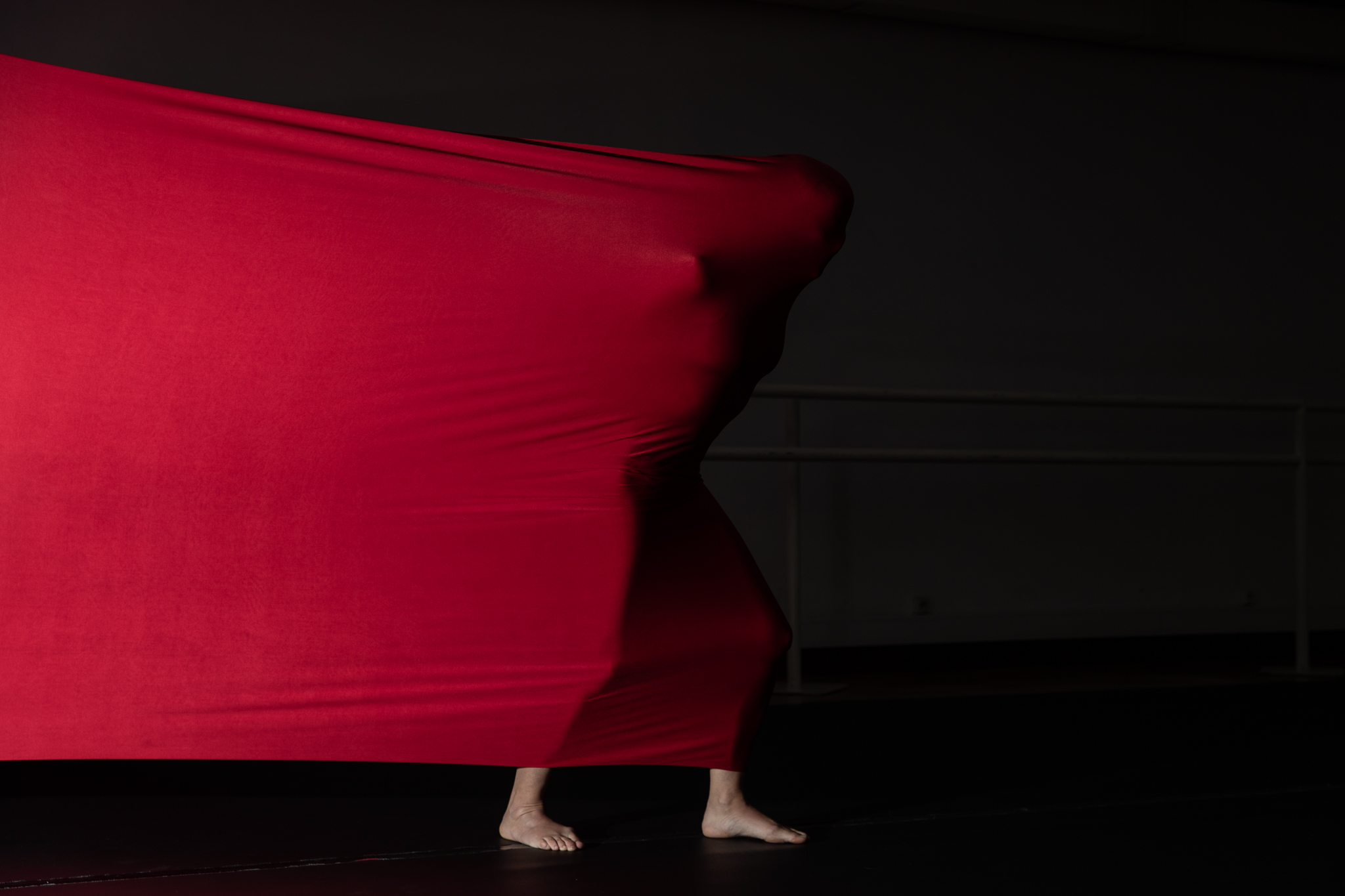

Como uma reverberação, as revoluções circulam neste espetáculo feito de camadas de memórias e de evocações artísticas e sociais. Revoluções da dança, da música, sociais e políticas vão despontando ao longo do espetáculo não aprisionadas numa cronologia histórica, mas em livres cruzamentos e justaposições temporais e temáticos. Alguns movimentos de vanguarda ou de gestos icónicos são convocados neste espetáculo, composto numa longa sequência como uma espécie de imagem cinemática onde corpo é protagonista, afinal motor de todas as revoluções como nos lembra os Comité Invisible. Neste andamento de evocações de mudança íntima e coletiva, o trabalho evolui de uma utopia (corpos movem-se em direção ao lugar onde tudo é possível, o palco) ao trauma (o retorno ao corpo através da nudez), que caracteriza muitas vezes o pré e pós-revolução.

É também deste modo que a intervenção dos Haarvöl se caracteriza: primeiro momento, antecâmara do espetáculo, o som que se propaga no pré-espectáculo; um segundo momento, a realidade e a pragmática da ação durante o espetáculo; um terceiro momento, o pós-espetáculo, a mesma instalação sonora, mas a música, agora, difere, evoca-se a fuga e o trauma. Revoluções conta ainda com uma seleção musical trabalhada em colaboração com a Digitópia, grupo ligado à Casa da Música. Da evocação de Eno a Reich, passando por Stockhausen, Parmegiani e Cage, a música vai reforçando uma dramaturgia de cruzamento e de deslocação, onde o sonho e o rumor tenham lugar.

É também deste modo que a intervenção dos Haarvöl se caracteriza: primeiro momento, antecâmara do espetáculo, o som que se propaga no pré-espectáculo; um segundo momento, a realidade e a pragmática da ação durante o espetáculo; um terceiro momento, o pós-espetáculo, a mesma instalação sonora, mas a música, agora, difere, evoca-se a fuga e o trauma. Revoluções conta ainda com uma seleção musical trabalhada em colaboração com a Digitópia, grupo ligado à Casa da Música. Da evocação de Eno a Reich, passando por Stockhausen, Parmegiani e Cage, a música vai reforçando uma dramaturgia de cruzamento e de deslocação, onde o sonho e o rumor tenham lugar.

Estreia

16 e 17 Novembro Teatro Rivoli, Porto, 2018

Itinerância:

Ílhavo 23 de Novembro 2018, 23 Milhas

Braga, 22 de Fevereiro 2019, Theatro Circo

Coimbra 18 de Abril 2019, Convento São Francisco